*This site contains affiliate links, which means I receive a commission when you buy. See my full disclosure.

In 2008, when I first moved to Sant Antoni, a neighborhood in the Eixample district (pronounced ‘eshampla’) of Barcelona, I was overwhelmed by the endless blocks and blocks of buildings. And on each block, everything looked the same – fruit stands, bakeries, supermarkets, banks. Then more fruit stands, more bakeries, more supermarkets, and more banks. Barcelona urban planning seemed boring.

Barcelona Urban Design

I didn’t think much of the fact that I could buy my groceries, make a bank deposit, select a decent public school, or have my kids play at a park all within a five to 10 minutes’ walking distance. But that’s just it. The proximity of community shops and services is just one of the genius elements of the city grid that makes urban living convenient and easy in the Eixample neighborhood. But there’s more…

Barcelona Urban Planning History

In the mid-1800s, Barcelona was a smaller, very dense area surrounded by walls (Ciutat Vella). With rabid congestion, increased epidemics and a high mortality rate, it was time to create urban solutions for healthier, more livable conditions for the people.

City developers were looking to create the “Eixample” of Barcelona, which in Catalan, translates to “extension”.

The godfather of Eixample’s city grid is urban planner Ildefons Cerdà. He believed in healthy everyday living through basic needs — among those are sunlight, ventilation, greenery, and ease of movement.

Elements of Eixample’s Urban Design

1. Eixample is 520 city blocks of parallel and perpendicular lines.

The uniformity and continuity of squares were designed to eliminate segregation of all neighborhoods. Cerdà believed in sanitary conditions for all social classes.

Critics of Cerdà’s plans claimed the uniformity was too monotonous. Buildings look identical and no outstanding structures as a landmark existed.

2. Each city block has chamfered corners, or xamfrà.

These quadrangular blocks with shaved-off corners, or peculiar octagonal blocks, serve a purpose. The 45º angle was determined by the degree that a steam tram was able to turn. It also eases fluidity of traffic as cars don’t need to slow down as much and allows a more comfortable turn for drivers.

Perhaps the disadvantage is for pedestrians. The placement of crosswalks obliges the walker to zigzag a street, instead of going down one straight line on a street.

Today, drivers take advantage of these chaflanes to park (and double park) their vehicles. A few chamfered buildings makes interesting angles:

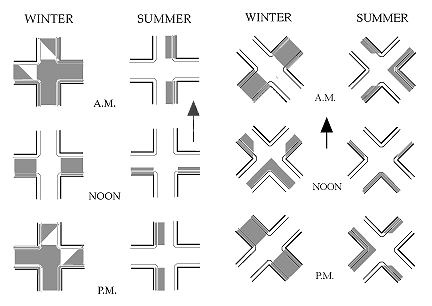

3. All the blocks are oriented northwest-southwest for maximum solar access.

The buildings are faced in a way to get excellent exposure from of the sun. Below, the images in the two columns on the right represent street intersections in the winter and summer and how the sun hits the buildings.

You can see they gets more sunlight than on the left-hand images, where the intersections lie north-south.

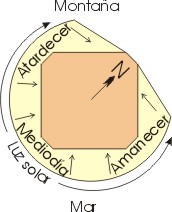

Below, the yellow parts in the image below represent sunlight and how it moves in a counterclockwise position during the daytime. Twenty meters between the blocks also provide ample space for light to pass through.

4. The buildings were supposed to be as tall as 16 meters in height as to not block the sunlight for other buildings.

Originally, buildings were supposed to be constructed until the height of the yellow square as shown above. The sunlight would penetrate all the buildings, including the bottom floor.

Cerdà’s plans were ignored. Buildings rose up to 24 meters, blocking the air and sunshine that was supposed to circulate.

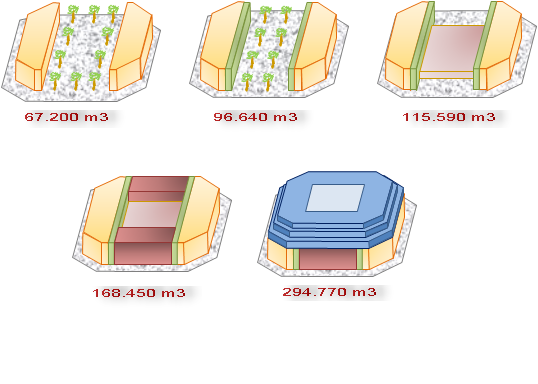

5. The original plan was to have two parallel sides of the block built up.

As seen in the first image, the block was supposed to be built only on two sides. Having this space ensured ventilation and sunlight, enabling more than 800 meters of green area in between.

Throughout time, you can see the constructed development of the city block — many became completely enclosed.

6. And the interior of the blocks was supposed to have an inner courtyard.

These would have served to be shady, intimate, recreational open space for the neighbors. Today, the interiors consist of workshops, shopping centers and car parks. There exists a few surviving interior garden community areas and swimming pool such as Jardins de la Torre de les Aigües and Casa Elizalde.

Luckily, an organization called Pro Eixample has taken charge of trying to recover green interiors. When a new part of a block is free, they take the initiative to convert the space into a green public space, where children and elderly people would most benefit. It’s a slow process to wait for an opportunity to arise.

7. Today, in 2019, Barcelona has superblocks, designated spaces almost exclusively for public use.

An urban pilot project, a “superilla” is a 9-city block in Barcelona. It’s a 3×3 block closed off to through-traffic (freight trucks, buses, etc.). Cars can drive through it with a speed limit of 10 km/hour. It’s meant to minimize car pollution and noise pollution, foster more walking, outdoor events, and day-to-day neighborhood activity like ping pong tables, benches, and race tracks on the street.

The first implemented Barcelona superblock is in Poblenou. Not everyone was on board because cars have to drive around the perimeter of the superilla, making it inconvenient for drivers. Today, the neighborhood of Sant Antoni has superilles, and others are being planned, including in Sant Antoni, Gràcia, Horta, Les Corts, Nou Barris, Sant Andreu, Sants, and Sarrià.

View this post on Instagram

Eixample is an emblem of the city: easy mobility where there are schools, hospitals, marketplaces, adding up to a high quality of living. And while much of Cerdá’s original ideas were quashed, his layout prevails. And that is enough for people to call it an urban design model.

I learned about Huasmann’s Paris in college. Fascinating article, Justine!

Wonderfull piece. By the way, I believe that the Catalan word for a chamfered corner is xamfrà (Castilian: chaflán).

Oh didn’t know that! I’ll change it in the post. Thanks!

Hi Justine,

Thanks for citing my article: Cerdà and Barcelona: The need for a new city and service provision.

Montserrat Pallares-Barbera

You might be interested also in:

Barcelona Cerdà Expansion: http://worldmap.harvard.edu/maps/Barcelona_Cerda_1860/CRD

This is a study about the benefit to population social wellbeing obtained by implementing the Cerdà’s Urban Expansion of Barcelona.

This is a map recreation of the urban evolution of Barcelona since 1860.

CITATION:

Pallares-Barbera, M. and Duch, Jordi (2012).Barcelona Urban Evolution from 1860. Harvard University: WorldMap. Read more:http://scholar.harvard.edu/montserrat-pallares-barbera/links/barcelona-cerd%C3%A0-expansion

Interesting to see how few schools, parks, and markets there were and how they’ve just filled in the gaps as the population has exploded. The grid system must help in planning. Thanks for sharing your work!

I have been trying to find any information about the designs on many Eixample buildings. Some appear to be stencils – but some of those are actually reliefs (very difficult to paint). Do you have any info or sources about that?

Hey Kelly, unfortunately no, I don’t have any sources on that. I do notice there are stencils, but most seem to be reliefs. At least that’s what catches my attention. 🙂

Thank you,Justine, I am from Shanghai.

The Eixample, Barcelona is a good example for high-dense development, especially for Shanghai China. But I don’t think the deep-plan flat buildings in Eixample are suitable for the Barcelona climates, the depth of the buildings reaches 22m-24m. The day-lighting and ventilation are problems, and over-hot inside in summer..

Do you think so?

Hi Aimin, I’m not an expert in urban design but I can say – yes, the flats get very hot in the summer. I lived in Eixample and I found it to be true. Not enough ventilation. You don’t get that Mediterranean breeze. Good luck!

Thanks for a great article! I just returned from a trip to Barcelona, staying in the Eixample neighborhood and loved it. I’m in the process of writing about it on my own blog “Live Cheap and Make Art USA” and will link this blog to mine on this post for folks to come for this lovely detailed explanation of this area! Gracias!

Hey Rosemary, Awesome! Eixample is so lovely. Even though everything looks the same from far away, there’s so much uniqueness when you look closer. I look forward to see the article on your blog!

Thank you Justine, for your kindness in sharing your impressions of this unique project with us. Blessings beyond measure!

Thank YOU, for such a simple, heart-warming comment, Angélica 🙂